Heavy the Head that Wears the Hat: Headgear in "Wolf Crawl," Weeks 1 & 2

Beginning a year-long journey through the head-bound fashion of "Wolf Hall" with the lost hope of Wolsey's papal tiara and a woman's humble caul.

In 2024, I - like many of you - participated in Simon Haisell’s “Wolf Crawl,” a year-long slow read of Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy. As someone who rereads Wolf Hall anually, discovering Footnotes & Tangents felt like a deliciously nerdy family reunion. So many people who share this literary DNA with me? Diving into these wonderful books each week for a whole year? Sign me up!

Towards the end of our slow read of The Mirror and the Light, I drew a connection between two shared moments with Tudor headgear: a gentleman’s hat and a woman’s white cap. (No spoilers, of course. Not yet, anyway.) Simon generously responded with interest, prompting a mini-discussion of hats and headgear in the novels.

Now, as I dive back into “Wolf Crawl” in 2025, I plan to track just that: hats, caps, crowns, tiaras, cauls, and everything in between. Unsurprisingly for a man so attuned to clothing, fabric, and material, Cromwell notices what people are wearing atop their heads quite a bit. (A twist on Wolsey’s prompt to “find out what people wear under their clothes,” perhaps.) In these first two weeks of our slow read, I found a few interesting references.

First, right away in “Across the Narrow Sea,” we are in Cromwell’s head as his head is nearly destroyed by his angry, likely drunken father. “Burst my boot, kicking your head,” Walter grouses on page 4, after Thomas, sprawled on the cobbles, notices that “the gash on his head - which was his father’s first efford” is bleeding. A bare head snags our attention, just as the twine in Walter’s boot has snagged.

Then, as we move forward to 1527, it is Wolsey’s head and its theoretical covering that catches Cromwell’s eye.

“The head that would have indeed worn the papal tiara, if at th elast election the right money had been paid out to the right people.” (p. 25)

Earlier, he describes Wolsey as having “A large head - surely designed to support the papal tiara - is carried superbly on broad shoulders…” (p. 19). To Crumb, Wolsey - the “man without price” - is the best of the Church and the best of men, with the vision of proper papal headgear to prove it.

A papal tiara, pictured above in a portrait of Pope Pius V by Palma il Giovane, is a once-common head covering for the head of the Catholic church. According to a blog post I found written by Fr. William Saunders, the first historical mention of a papal head covering was in an account of the life of Pope Constantine, who served from 708-715. At that time, it was likely more of a white “papal cap,” but the “tiara” description held regardless of material. Within a century, the cap gained a golden circle, which evolved into a toothed golden crown by the 1200s. At this time, it was more commonly called a “tiara,” and may have also included two white fabric fans at the back, possibly representing ancient Greek Olympic headgear in a reference to St. Paul’s “I have run the race, I have kept the faith.” (2 Tm 4:7-8). Eventually, the tiara had three crowns, as depicted in the painting above, which signified layers of papal authority on earth or as a sign the Church’s reign over purgatory, the realms of man, and heaven itself. If anyone could handle that level of authority in Cromwell’s eyes, it was Cardinal Wolsey.

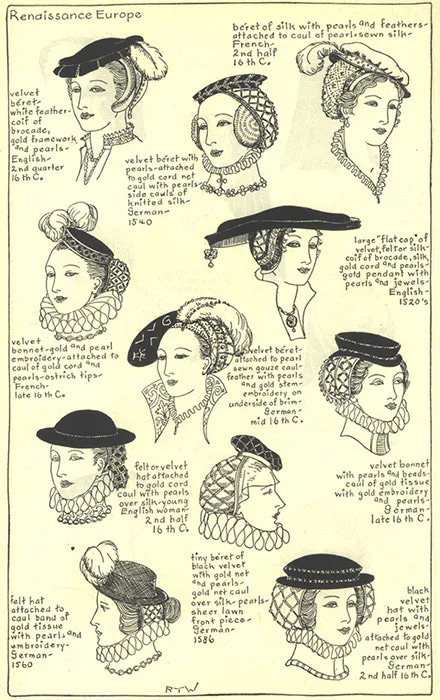

Later, in “At Austin Friars,” we meet the lovely and down-to-earth Liz Cromwell, who often works at weaving “…fine net cauls for the ladies at court” (p. 35). The image above, a collection of reproduction French hoods, shows several examples of a Tudor caul below the hood’s headband. A caul, like the snood often seen at Renaissance faires all over the country, was a bag-like headdress often worn by girls and young women. The fabric of the caul may have matched a woman’s dress, or it may have been made of black velvet or silk covered with gold netting. Essentially, it was a knitted or fabric hairnet, and may have likely been attached to such structures as a French hood. There are interesting variations from across contemporary Europe, such as the Spanish cofia, the Italian balzo, or the German fashion of a knitted hairnet worn with a knitted veil or even a broad flat hat. (Thank you to the Elizabethan Costume Page for its meticulous research!)

And then, our first fateful meeting with Liz’s white cap:

Her hair is pushed under a linen cap and her sleeves are turned back.’ (p. 44)

The linen cap, sometimes called a coif [pronounced “qwaf”], was a woman’s most common and most-worn head covering, likely worn all day apart from brushing or washing one’s hair. A plain linen coif was the foundational hair garment for women, and as the Tudor period went on, it might be topped by a cap, hood, veil, or even a turban. It served as a modesty garment, kept one’s hair neat and tidy, and may have even helped prevent lice infestations. (Shout-out to The Pragmatic Costumer for their research and images!)

Finally, these chapters mention the hunting scenes of Wolsey’s tapestries, so recently and roughly handled by Norfolk and Suffolk’s men, as being filled with elegantly attired men and women. Specifically,

…the ladies on horseback with jaunty caps. (p. 49)

There will be many caps in these chapters and pages, so I’ll hold off on deeper discussion or historical research for now. The connection between caps and hunting, a rich one in these novels, will tempt us another day.

Yours in headgear and happy reading,

Analise

Thank you for your hard work. I am looking forward to learning a lot about this subject! I am easily old enough to remember the advertising slogan “If you want to get ahead, get a hat”—but for my first job interview my prospective employers assured me that “Ladies did not have to wear hats or gloves“. So we, as a culture, have rather rapidly lost any deep understanding of hat-wearing as a signifier of status (with the exception of the Royal Family, and perhaps MAGA hats in the USA?).

I love this! Thank you for your research and for sharing.