We’ve reached week 6 of Wolf Crawl, and us readers are wending our way through the first half of “Entirely Beloved Cromwell.” We begin this week’s tour of the headgear of Wolf Crawl with a fan favorite, Thurston, master of the Cromwell kitchens.

Thurston takes off his hat again, and turns it inside out. He looks at it as if his brains might be inside it, or at least some prompt as to what to say next. (205)

Thurston is one of many characters to whom Crumb poses a fateful question: “Do I look like a murderer?” As

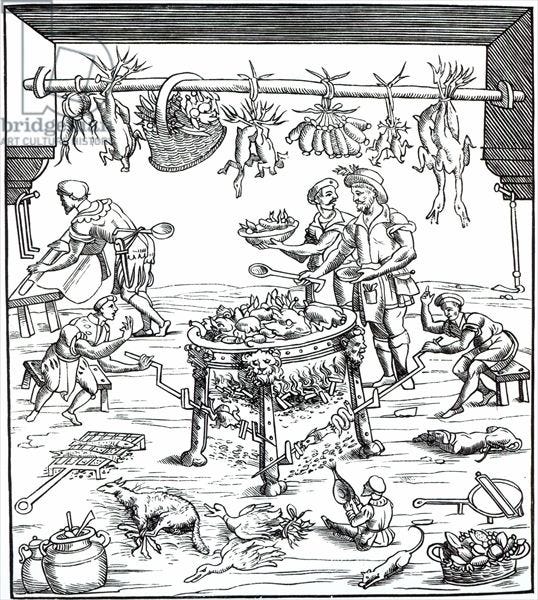

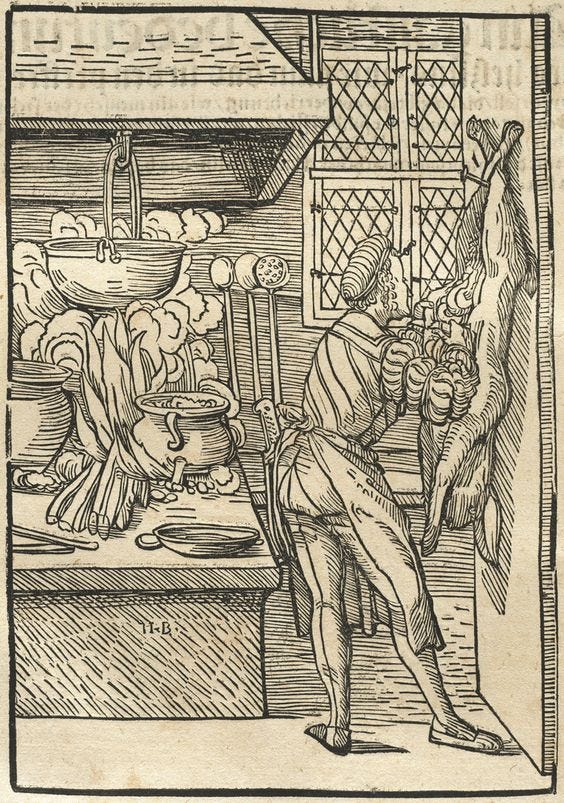

reminds us in this week’s Wolf Crawl post, while Thurston doesn’t quite agree with that impression, he does acknowledge that Master Cromwell “always look[s] like a man who knows how to cut up a carcass.” The description of Thurston taking off his hat implies that it’s normal for him to wear one in the kitchen, and this sent me flying through the internet and its many corners.I found the image above in a wonderful blog post from Andreadoria at The Vulgar Crowd entitled “The 16th century cook and his attire.” Andreadoria shares a number of visual insights on what a cook might wear, drawn from their own footnotes and tangents in image searching.

…We see that there is a fashionable difference between an apron for a male or a female. The male apron seem to be extremely simple – just a squared piece of linnen fastened with a knot, and quite short.

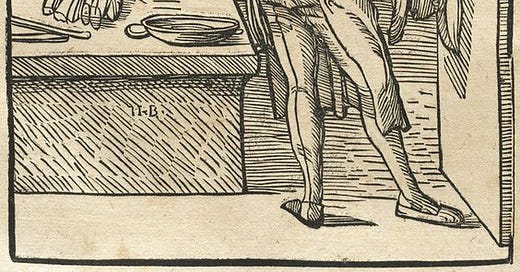

…Quite a few of the depictions of our culinary artists portray them with fashionable clothes – it is slashed and well fitting, many with the hypermodern “kuhmaulschuhe”, the cow mouth shoe. I would like to point out that these cooks are most probably some sort of court cooks, or working for lords with a more lavish taste in food.

Also we see quite a few not only stylish, but also hygienic, hair nets and hair gears on our male chefs.

Another of the images they found was this sketch of an Italian kitchen, modeled on a 1549 woodcut by Christoforo di Messisburgo:

The modern chef’s uniform, with its starchy white aprons and toques, is attributed to Marie-Antoine Careme in the early 19th century and popularized in the West by Escoffier. Interestingly, the toque itself may date to the 16th century, and its one hundred folds are meant to represent the chef’s diverse sets of skills. Not to mention that height of the hat = height of power and influence in the kitchen. And one alleged story from Henry VIII’s reign explains why Tudor-era chefs like Thurston would have found a hat to be a necessary accessory, as we learn from the Escoffier School of Culinary Arts:

One of the main theories is that the chef’s hat came about as a way to keep hair out of food and maintain hygiene and cleanliness in the kitchen. According to one origin story, King Henry VIII supposedly beheaded a chef after finding a hair in his meal, so all the chefs after him were ordered to wear a hat while cooking.

In that same Escoffier article, the author cites Heidemarie Vos’ Passion of a Foodie as a source dispelling the idea that the only function of a chef’s hat was to keep hair out of the face and out of food:

She cites another origin story that dates back to circa 146 BCE, long before the French adopted the hats.

When the Byzantine Empire invaded Greece, Greek chefs fled to nearby monasteries for protection. While there, they attempted to fit in by adopting the garb of the monks, including a large stovepipe hat. Even after the Byzantines retreated, Greek chefs continued to wear the hats as a form of rebellion and a sign of solidarity.

It’s perhaps that symbolism and sense of fraternity, Vos argued, that led other chefs, including the French, to adopt the hats in their own uniform.

Food for thought. (I told you there would be more terrible puns.)

During Cromwell’s first meeting with Anne, we also have our first meeting with the famous French Hood. When asked by the ladies of Austin Friars how Anne was dressed, Cromwell responds immediately:

Ah, I can tell you that … For her headdress Anne affects the French style, the round hood flattering the fine bones of her face. (207)

At the beginning of the encounter, as Cromwell spends Anne’s allotted five minutes arguing for Wolsey, he notes how closely Anne attends his words, with the full force of her attention. Even though,

He has always wondered how well women can hear, beneath the muffling folds of their veils and hoods. (202)

Even the smallest or least visible of Anne’s fashion accessories does not escape the attention of both Cromwell and her ladies in waiting. Their hoops & thread are hard at work as all of her clothing, even “her coifs and veils” (203), are being embroidered with her new coat of arms.

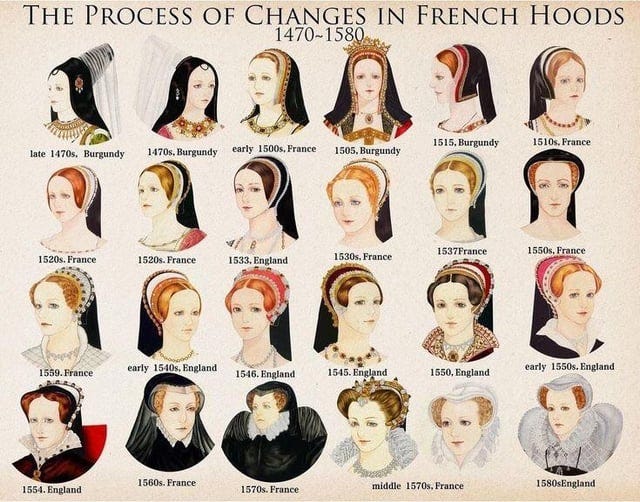

Much like syphilis being called the “French Pox” in England, the “French Hood” was likely only known by that misnomer in England. It was also commonly seen in the Low Countries, and similar hoods have shown up in images from contemporary Austria. Anne is often credited with its introduction, but researchers are more likely to cite Mary Tudor (the former Queen of France, as Suffolk reminds Cromwell during their visit to the palace kennels) as introducing the fashion to England.

I found a remarkably detailed examination of the French Hood on French Renaissance Costume.com. In the 2017 article, author Alliette Delecourt “deconstructs” innacurate fictional portrayals in film & television, as well as reconstructions of French hoods, by citing period portrayals in art and scuplture. It’s a deep dive, but a great tangent.

French hoods sat flat on the head during Anne’s time, and (like the Gable hood) were built as multi-layer headdresses rather than a single piece of headgear. The famous “crescent” shape was created by the construction and placement of the layers, which Delecourt lists in detail. (This is the 1510-1530s version that Anne and her ladies in waiting would likely have worn):

First, a white undercap, as we have seen earlier in Wolf Hall. This would be mostly invisible once the piece was fully pinned and assembled on the head, other than a frilled or finely transparent bit in the front.

Then, a second cap. Mostly like this was white or red, but could also be black. Ornamentation might include a decorative front edge (royal ones might have jewels). It may have also had a chin strap, as we see in the recent Tudor film “Firebrand.”

The hood itself. Also likely black, but perhaps with a colorful lining; the “veil” at the back would be longer at the sides and continued to lengthen during this period. It would often have a decorative “billament” at the front as the Gable hood did; historians are unsure whether this was a separate pinned piece.

The decision between French vs. Gable hood was more than just a stylistic fashion trend as Henry’s reign went on, but we’ll cross that bridge (or pin that hood?) when we get to it.

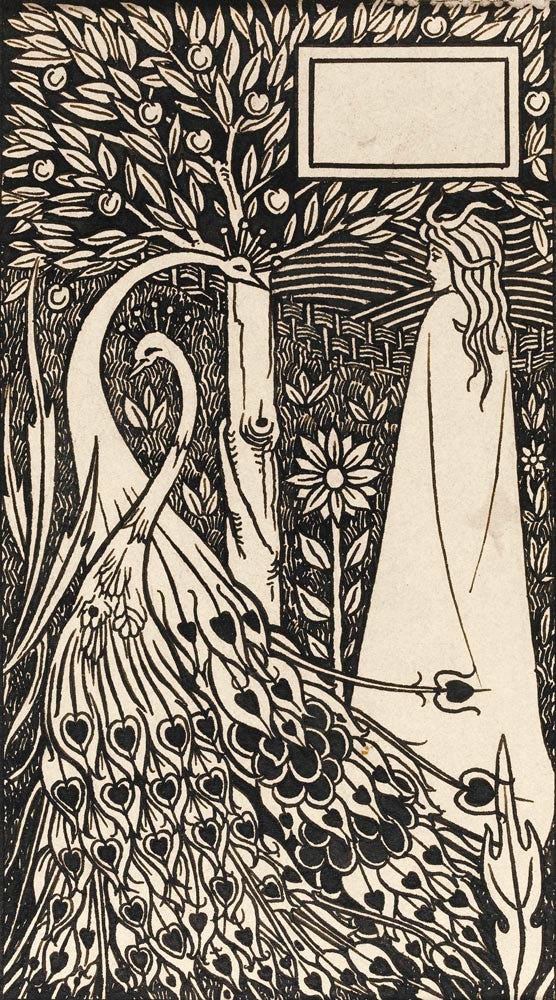

There is a brief mention of strange headgear as Gregory is reading his new copy of Malory’s Morte d’Arthur. We see a curious illustration:

On a high-stepping horse is a man with a mad hat, made of coiled tubes like fat serpents. Alice says, sir, did you wear a hat like that when you were young, and he says, I had a different color for each day in the week, but mine were bigger.

These days, the best known illustrations for Malory’s text are those of Aubrey Beardsley in the late 19th century.

It’s proven difficult to find archival images from editions prior to the Beardsley printing. Although, you can buy the “Winchester Manuscript” of Malory’s text with period-era artwork & illustrations via Oxford University Press. Perhaps a future purchase will lead to a return to these “truth…lies…all good stories” for us here.

And finally, at the tense, strange dining table in Chelsea, Lady Alice grabs our attention. I find Alice to be a deepy sympathetic figure. Perhaps I’ve simply bought into Cromwell’s (admittedly somewhat partial) point of view of the More family at table, but I find the family patriarch to be a frightening, cruel figure in that sly, roundabout way that Crumb clocks immediately.

Lady Alice is the subject of our final reference this week:

“Eat, eat,” says More. “All except Alice, who will burst out of her corset.”

At her name she turns her head. “That expression of painful surprise is not native to her,” More says. “It is produced by scraping back her hair and driving in great ivory pins, to the peril of her skull. She believes her forehead is too low. It is, of course. Alice, Alice,” he says, “remind me why I married you.”

“To keep house, Father,” Meg says in a low voice.

“Yes, yes,” More says. “Alice frees me from stain of concupiscence.” (211-212)

We cannot see Alice’s ivory pins in this portrait, but we know that women had their “pin money” and used pins to fasten a number of their personal wear and fashion. Generally speaking, pins were plentiful and cheap. As Ruth Goodman tells us in How to Be a Tudor.

In the 1580s they could be purchased for as little as two pence per thousand for small fine ones, with thicker and longer dress pins fetching anything from six pence per thousand to three shillings per thousand. As well as being manufactured [in England], they were imported through the port of Antwerp into London in vast quantities.

Alice, however, has ivory pins, which — unless you’re looking at ivory from an elephant in the Tower of London menagerie — was not exactly a locally grown product. The history of international ivory trading and elephant poaching is long and complex; the Met in New York provides a concise summary accompanying gothic-era ivory religious carvings in their collection. 1 This passage is also a callback to our earlier discussion of hair color & style preferences, e.g. low vs. high foreheads.

It’s been an exercise in reflection, all these years of reading & rereading the novel, to reconcile my teenage Catholic understanding of the “Man for All Seasons” with Mantel’s portrait through Cromwell’s eyes. An exercise that is strange, surreal, and double, like how Cromwell sits with both the painted Mores and the family in the flesh. The truth might lie somewhere in the middle of the vaunted saint and the misogynistic fanaticist, but I have come to appreciate the complexity of these disparate portraits as parts of a more real, more human whole.

Until next time! -Analise

I Really felt for Alice as well. Thanks for all the interesting links and information. So much to enjoy